By Andy Marks, Western Sydney University

A gambler would probably feel the odds favour a Labor win at the upcoming New South Wales election. But, as Scott Morrison proved in 2019, underdog status is prized in politics. Favouritism brings its own challenges, especially when the game takes an unanticipated twist. In this setting, the wide path to victory can quickly become a narrow track to defeat.

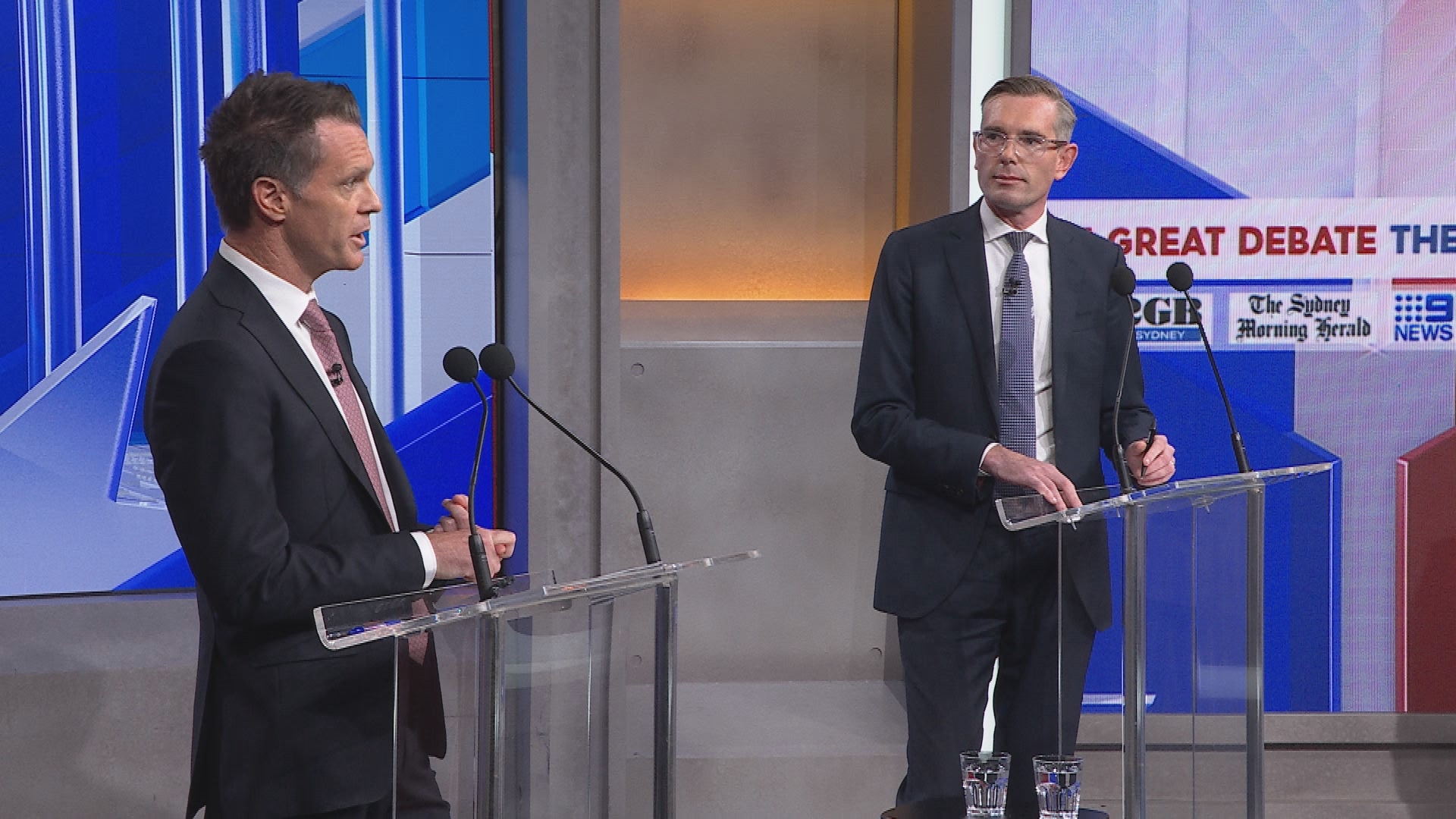

NSW voters go to the booths on March 25 with Premier Dominic Perrottet seeking to lock in 16 years of Liberal-National incumbency. The Labor opposition under Chris Minns is polling well. Despite this, Perrottet isn’t playing to type.

This campaign is recasting the state’s typically combative political culture. Peace has broken out. Major campaign promises, from both sides, are converging on a shared political centre. Be it toll relief, health infrastructure, energy vouchers or other rebates, only strategic nuances separate the two.

Funding commitments, too, are broadly on par. The Coalition’s “future fund” promises education and housing co-investment to individuals, while Labor’s “education future fund” directly targets the schools system.

On public sector wages, neither side is promising increases. Both leaders will thin the ranks and freeze the pay of senior public servants. And Perrottet has ruled out further privatisation, ending nearly a decade of “asset recycling” and bringing the Coalition into line with Labor.

With commonality abounding, real difference is emerging on unanticipated terrain. The NSW cabinet’s decision to introduce cashless gaming within five years is providing Perrottet a moral profile that typically takes time for a new leader to build. It also acts as a reset following revelations of his Nazi costume choice at his 21st birthday.

In contrast, Labor won’t back gambling reform, seemingly untroubled by the issue from a campaign standpoint. These divergent stances could weigh on undecided voters wondering what kind of a premier Minns might be. Would he stand up to powerful lobbyists? It’s not an insignificant question given Labor’s past in NSW. It may be a factor in marginal electorates.

Several seats in western Sydney are shaping as tight contests. With roughly one-third of the total votes cast at the election to be lodged in Sydney’s west, there is no path to victory for the Coalition or Labor without the region’s support.

East Hills, which the Liberals hold by just 0.1%, is a campaign focal point. In an announcement confined almost entirely to social media, the premier committed $1.3 billion to construct a hospital in the electorate.

Ordinarily, a hospital pledge would be a widely promoted commitment. Keeping it local may be a deliberate strategy to emulate isolated success at last year’s federal election. In the western Sydney seat of Lindsay, the federal Liberals bucked the national trend and secured a positive swing. Hyper-local, street-by-street campaigning fuelled that unexpected surge. https://www.youtube.com/embed/j-mbz2y5ksM?wmode=transparent&start=0

Lindsay overlays the marginal NSW seat of Penrith, where former minister Stuart Ayres is defending a margin of just 0.6%. Here, too, the Liberals are upending wider campaign tactics for a local pitch, with the help of former premier Gladys Berejiklian.

Continuing his moral stance, Perrottet endorsed the Independent Commission of Corruption’s investigation of her and continues to disavow her it’s “not illegal” rationale for pork-barrelling.

Other factors ramp up the unpredictability. The new seat of Leppington – nominally Labor (1.7%) – takes in many highly mortgaged areas of Campbelltown, Liverpool and surrounds. The pace of housing development has far eclipsed the construction of education, health and transport links.

Similar growing pains are evident in electorates like Riverstone, where existing services are unable to cope with surging housing estates. Labor is, accordingly, promising to address these challenges, committing to a range of investments such as a $700 million hospital for Rouse Hill.

The retirement of several senior Liberal members brings additional opportunities for Labor in key seats. Kevin Connolly in Riverstone and Geoff Lee in Parramatta are departing, along with cabinet members David Elliott, Brad Hazzard and Rob Stokes.

Stokes’ seat of Pittwater is among a clutch of northern Sydney electorates facing challenges by independent candidates. However, a repeat of the federal “teal wave” is unlikely, given the optional flow of preferences, and mitigating budget measures from Treasurer Matt Kean with a focus on women and sustainability.

In the regions, the transition to clean energy is challenging the Nationals’ hold on the Upper Hunter, while the retirement of Liberal Shelley Hancock has put the seat of South Coast in the frame for Labor. And the Nationals’ grip on the bellwether electorate of Monaro will be closely watched, with former Labor representative Steve Whan making a comeback.

This is an unusual election. Conventional analysis – and the bookies – suggest a Labor win, likely in minority government. But the Coalition are rolling the dice in narrowly targeted areas and on atypical issues.

While the heat has gone out of NSW politics, many voters will struggle to make sense of the peace. Others are understandably sceptical it will last.

Andy Marks, Pro Vice-Chancellor, Strategy, Government and Alliances, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.